John Gooding came knocking on my door around 7am. I had crawled out of bed around 5am to film the morning train come into the station but I had gone back to bed so I was lying half awake, half in my sleeping bag.

"You guys want to go out in the boat today?" John asked.

"Lets do it," I told him.

"I'll be back in 20 minutes after I put gas in the tank."

So I lingered for another 10 minutes, drank some water and got my camera gear ready to go.

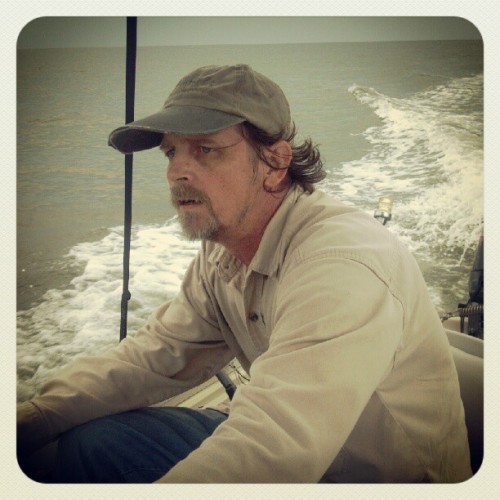

The three of us - Ben, John and I - were out in the water within half an hour. Ben is the associate producer acting as sound engineer. I'm the cinematographer. John is our subject. He was a hero during the response to Katrina and today, he continues to shine a light on the environmental fall out following the deepwater horizon oil spill.

It was a bit crowded on the little outboard whaler boat and water was splashing in over the hull. I locked my camera gear away in the Pelican case and lamented all the moments I could not capture on video.

"If you want, we can go up river," John offered. "We don't have to go out to Cat Island today."

I pulled the camera back out when we got to Cat Island. Birds were diving into the water and eating fish. Even 50 feet out, we had to be careful about beaching the boat so we couldn't get in very close. The kit lens on my NEX-VG10 goes out to 200mm but the constant tilt and roll of the boat limited my ability to capture the story unfolding in front of me.

Temperature of 85 degrees. Mild humidity. We couldn't have picked a better day to go out to the island.

I put the polarizer and UV filters on and did my best to keep up. As we pulled the boat on shore, John jumped out to look for tar logs. He'd run out ahead of us pretty far and I wore myself out trying to stay ahead of him.

In response to the oil spill, BP dumped millions of gallons of neurotic dispersant to mitigate the disaster. According to BP, the problem is all fixed. According to others, like John Gooding, the oil is still out there and continues to wash ashore in the form of tar logs. Little globs of tar and sand - roughly the size of a 40oz can of malt liquor.

John was picking everything up and smelling it. Little black logs. Most of the time it was charred organic material like burned logs. Sometimes it was a tar log. We also found a hunk of brown sticky rubbery god-knows-what.

Right as we were getting ready to leave for home, we saw storm clouds brewing on the horizon. Specifically, storm clouds blocking our path back to the mainland. We decided it was better to wait out the storm on land than to meet it in open water so we stayed put.

We watched as waterspouts dip down from the sky. Fortunately, the lightening broke or we would have been more anxious about sitting in the path of the storm. And as it approached, we could see the storm front as physical as a locomotive, barreling down on us. I filmed for as long as I felt comfortable and then I put the camera back into the case.

Birds went crazy. Bugs went nuts. Our sunny day was quickly obscured by the clouds rolling in. The wind picked up and tossed pellets of rain and saltwater into our eyes. And I didn't get any of it on film.

After the storm passed we noticed the tide was beginning to change and that our boat was now high in the sand. So there was that to deal with. Racing against time, we got to pushing the boat back to the water. We were soaked up through the soles of our shoes and as the sun came back out the wind dried our shirts and left chunks of sand on our skin and in our hair.

It pains me as a documentary filmmaker to sit back and let these experiences happen to me - especially the emotionally intense moments - but perhaps it is important to let some of these moments go. With my eyes free from the frames of the picture, I am able to see the bigger story.

That is, how people meet the challenges life presents to them if that be literal storms or the metaphorical storms of the human condition.

The next day, as John worked on his boat engines, the story manifested itself to me again. He was trouble shooting an engine that wouldn't start. He said when engines sit for a long time, the gasoline turns to varnish and blocks the fuel from igniting properly. The puzzle was in finding the buildup and flushing it out.

With him today, John brought his daughter and his Slavic son-in-law to hand him screws and generally learn everything he knows about boat maintenance.

"Its useless. This engine is not going to start," John's son-in-law declared.

Well, five minutes later he had it started. And I captured the moment. Where other people are quick to give up, John Gooding stays with his problems until he sees that they are fixed. Its an admirable trait. And its an incredible feeling, as a cinematographer, to find that trait that really defines a person and to capture it in pictures. Its incredibly rewarding.

Friday, July 13, 2012

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment